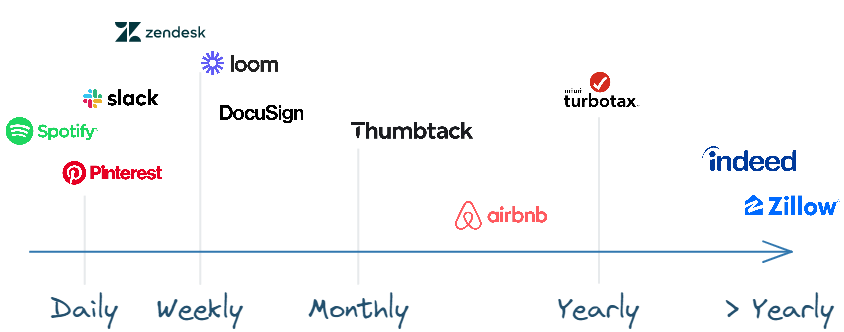

Core motivations say why users any solution to solve their problem, i.e what they gain from solving it at all. Differentiators say why users choose your product. What makes you stand out compared to the alternatives?

Understanding why a user picks your product helps uncover the core actions that create value, define your positioning and messaging that differentiate your product from the alternatives, identify the value metrics that you charge for — and many other elements of your growth and product strategy.

A lot of companies struggle to come up with compelling differentiators. Simply stating “we are better”, “our product is easier to use”, or is of “higher quality” doesn’t cut it.

Those statements are too generic, too nondescript, too common. They are not convincing. To convince potential users, your positioning has to highlight contrast and be specific.

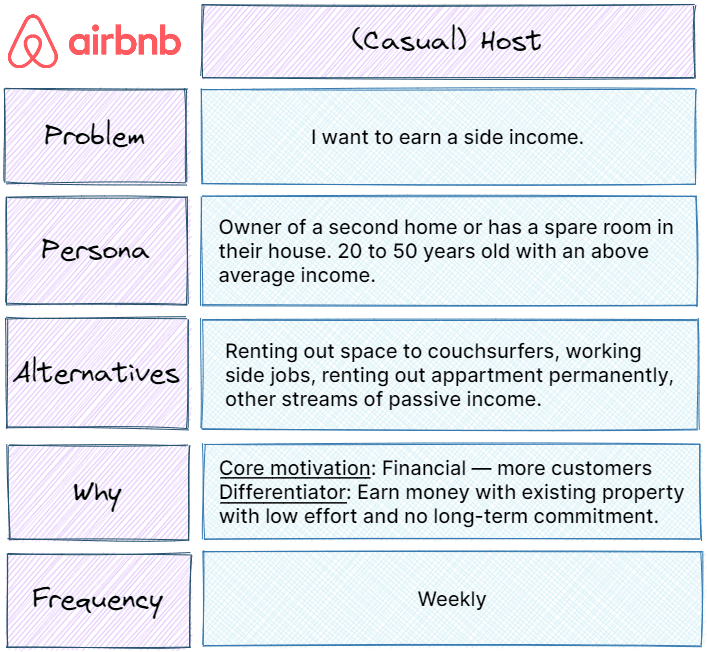

- Airbnb: I can earn a side income through property I already own, with low effort and no long-term commitment.

- Pinterest: I can find things on Pinterest I can’t find anywhere else. It’s also easier to discover more content based on what I like.

- Loom: It’s way faster, more personal, and more creates more effective messaging than the alternatives. Also, it’s asynchronous so we don’t have to agree on a meeting time.

- Thumbtack: I can access a larger pool of home professionals and can compare quotes from multiple professionals.

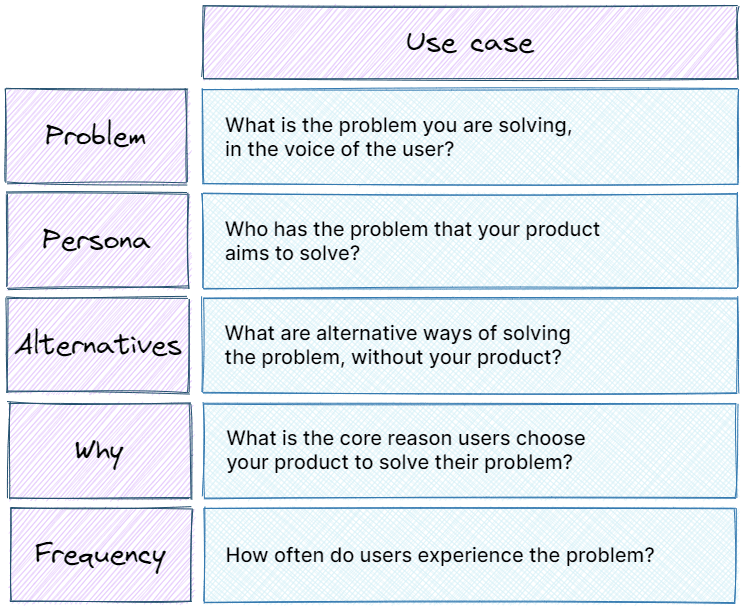

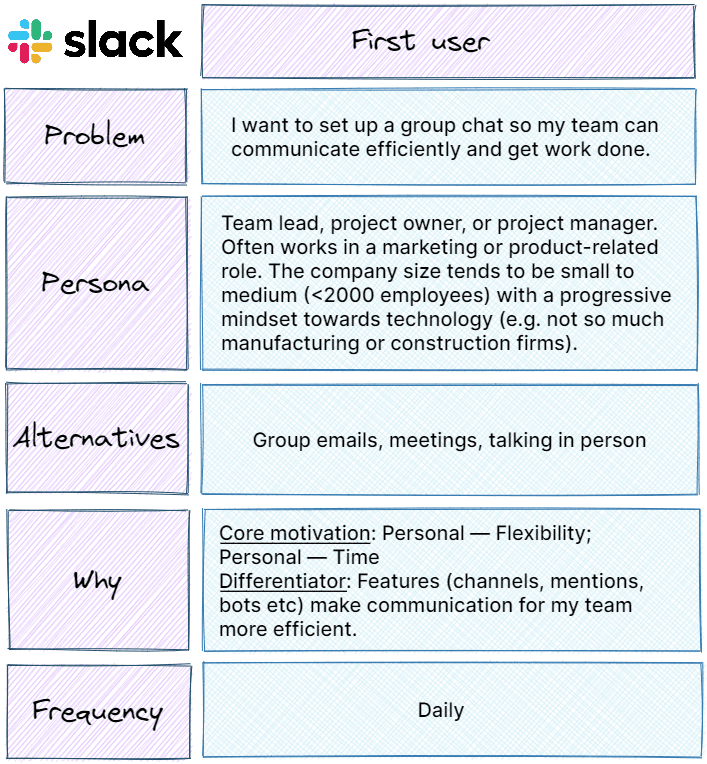

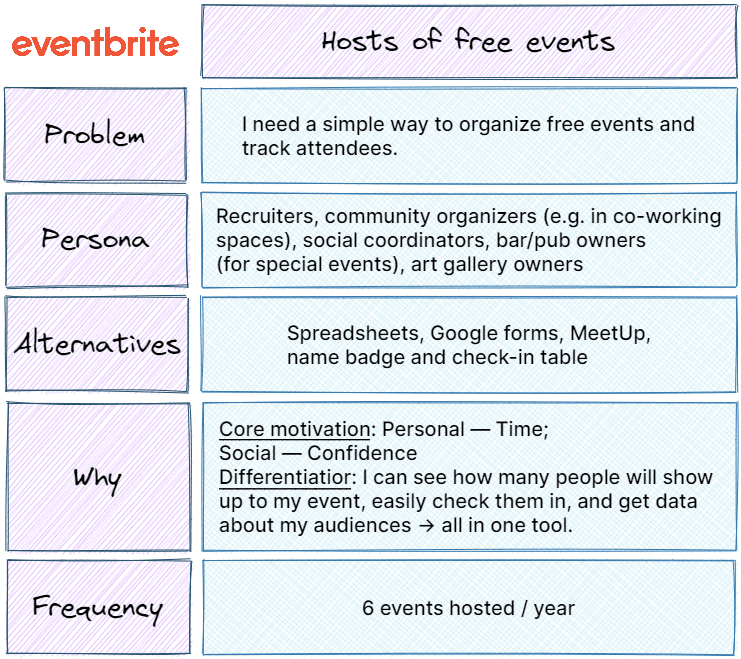

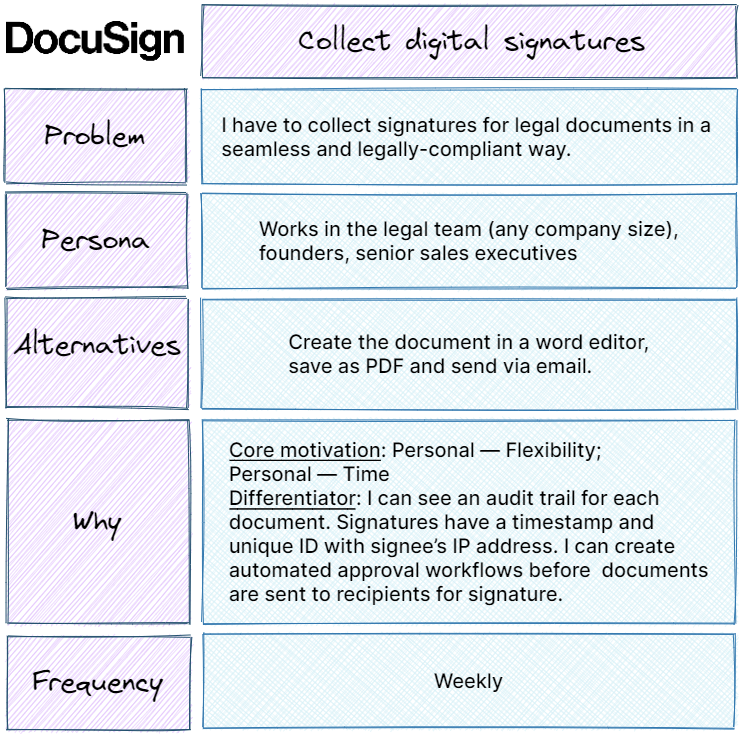

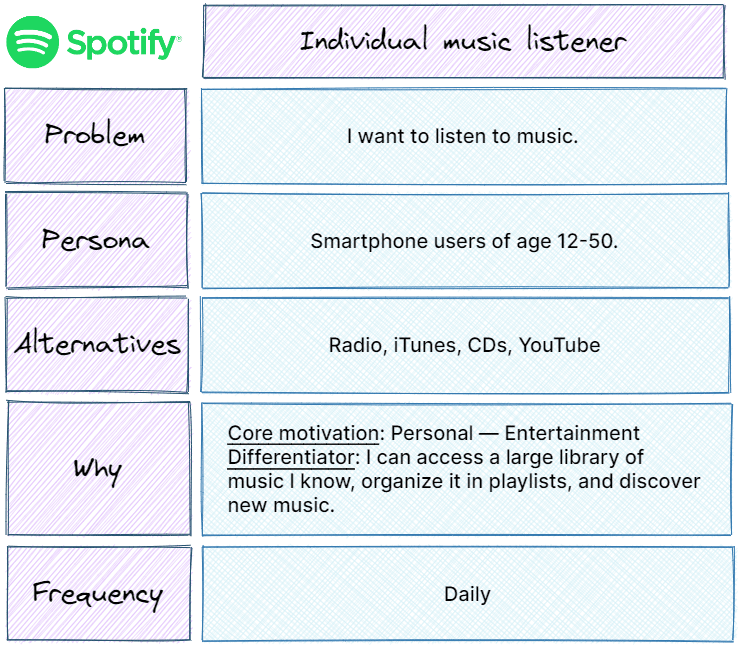

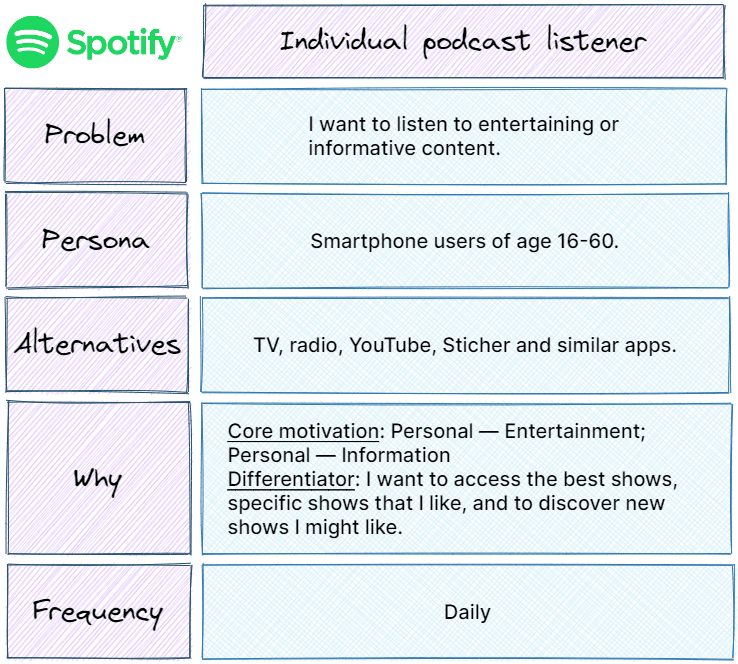

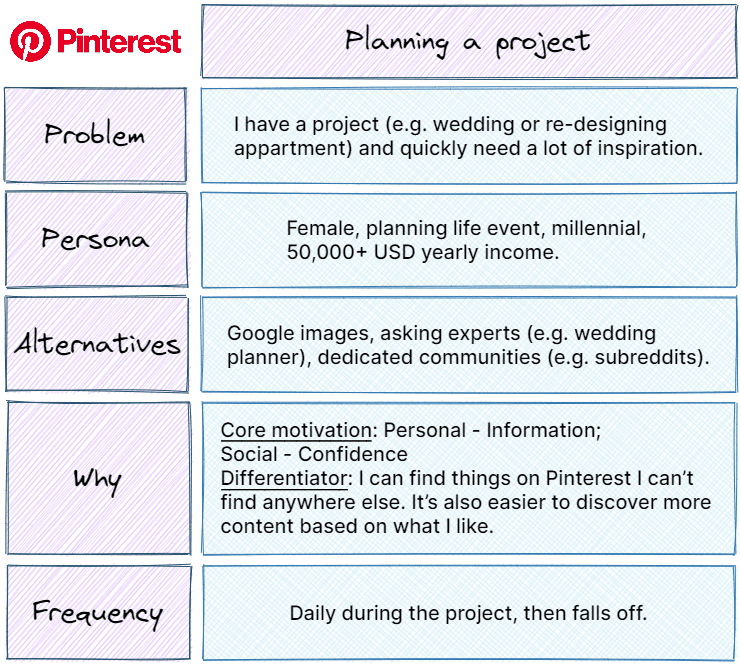

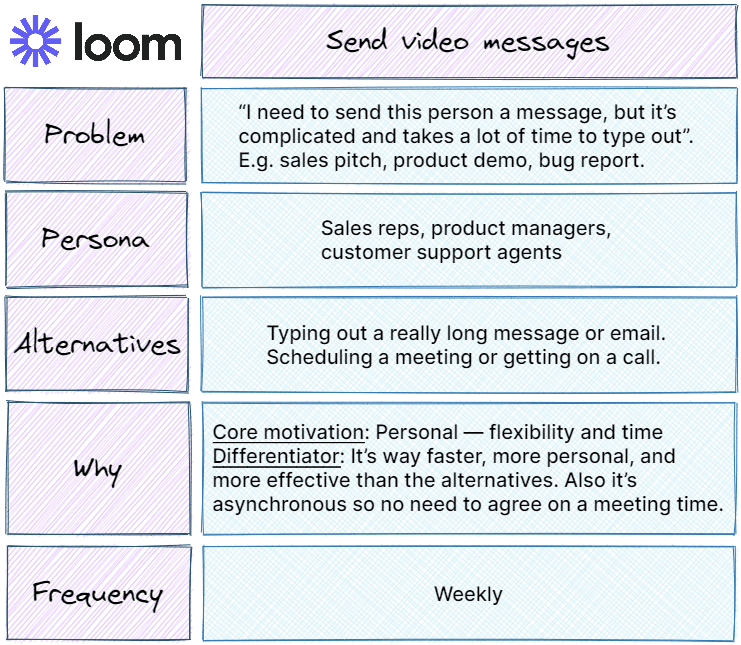

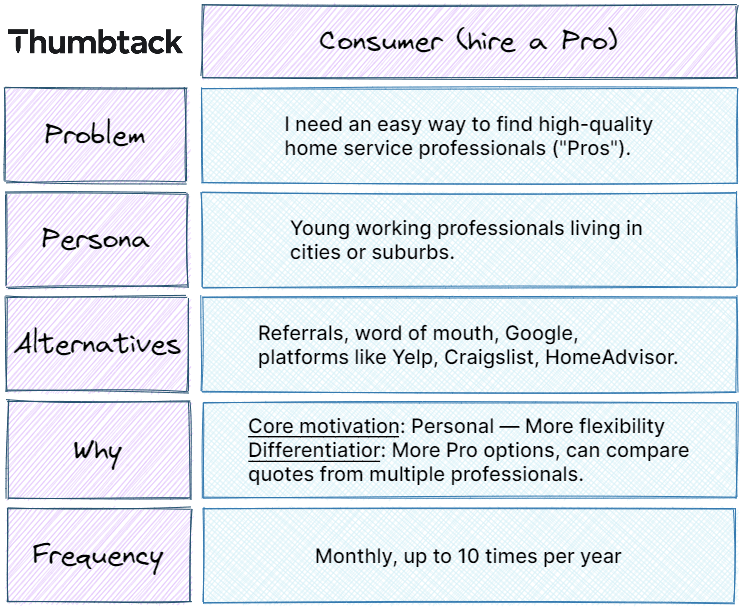

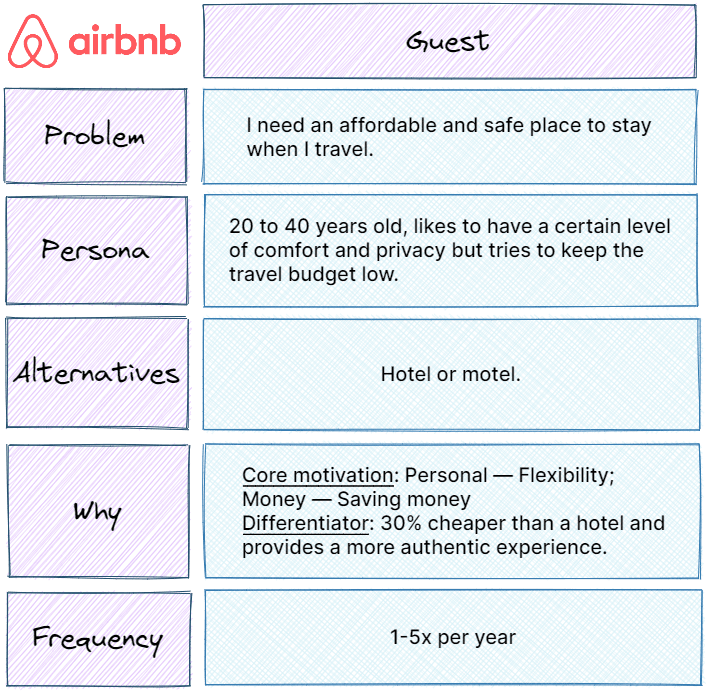

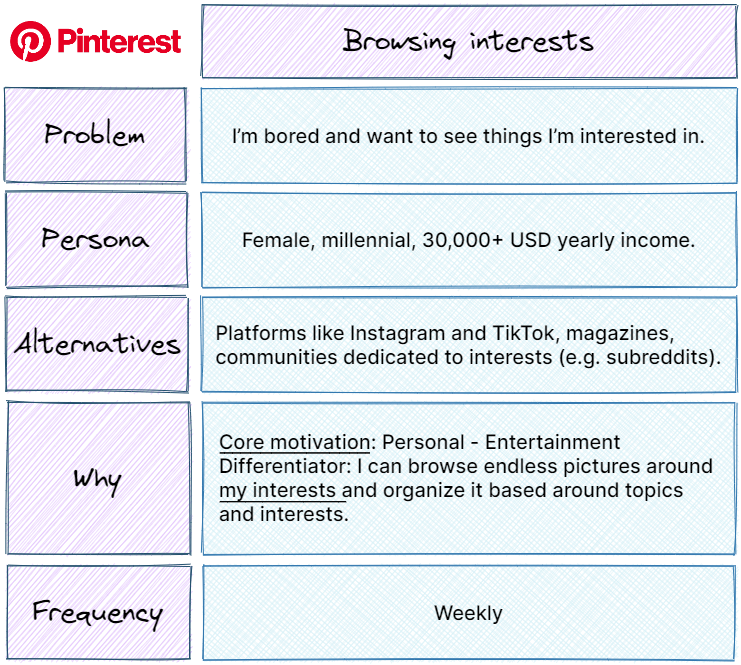

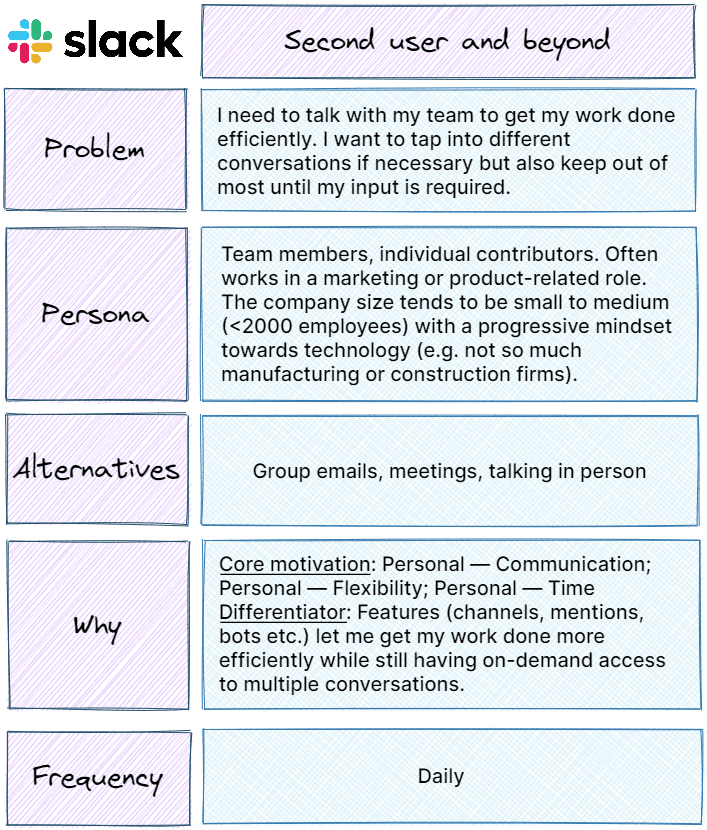

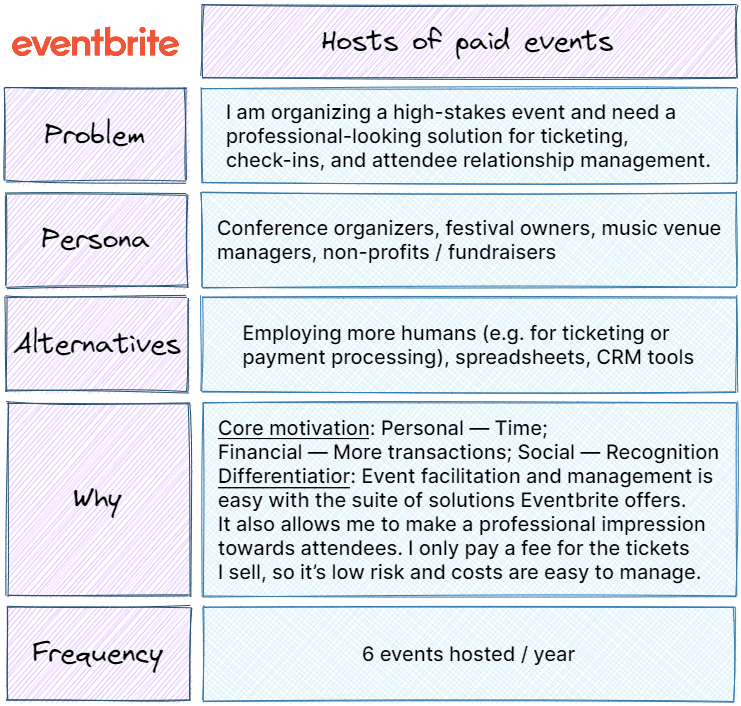

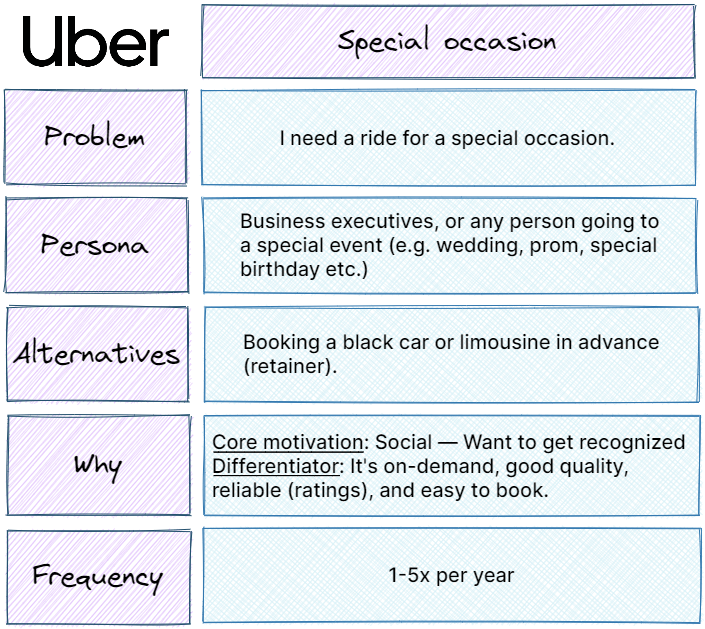

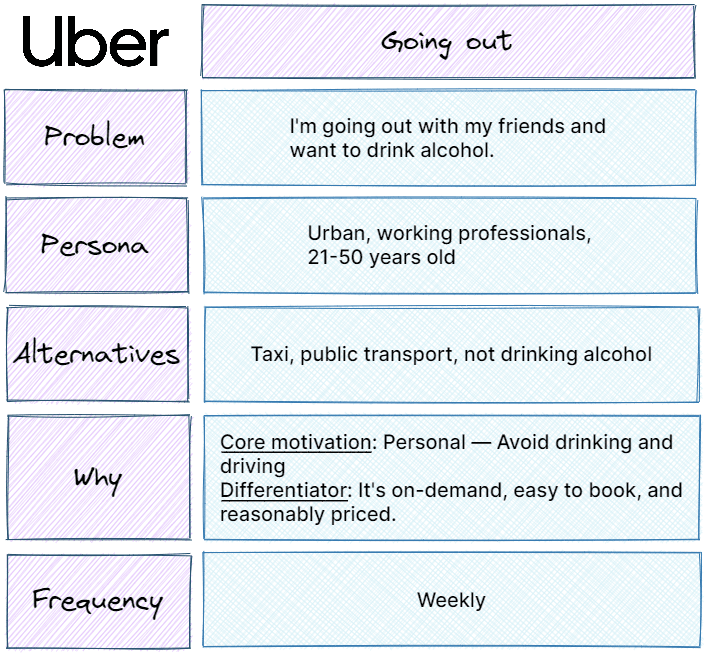

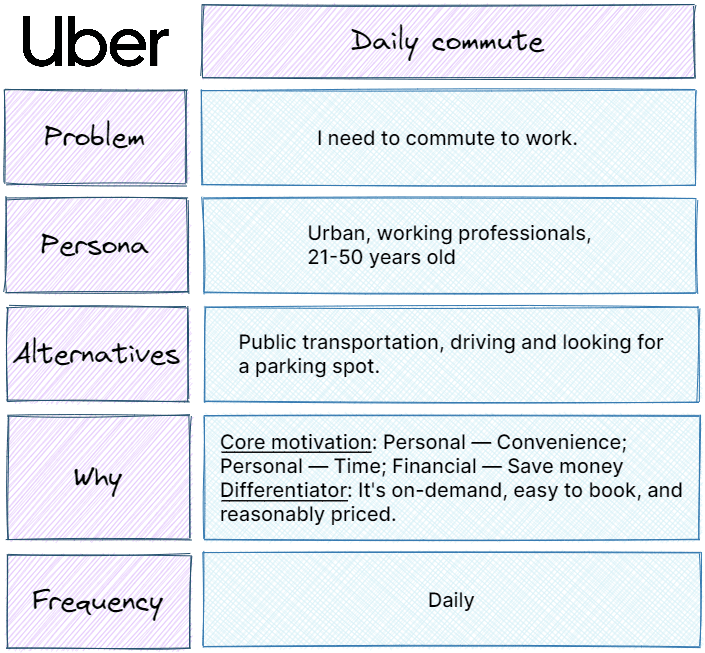

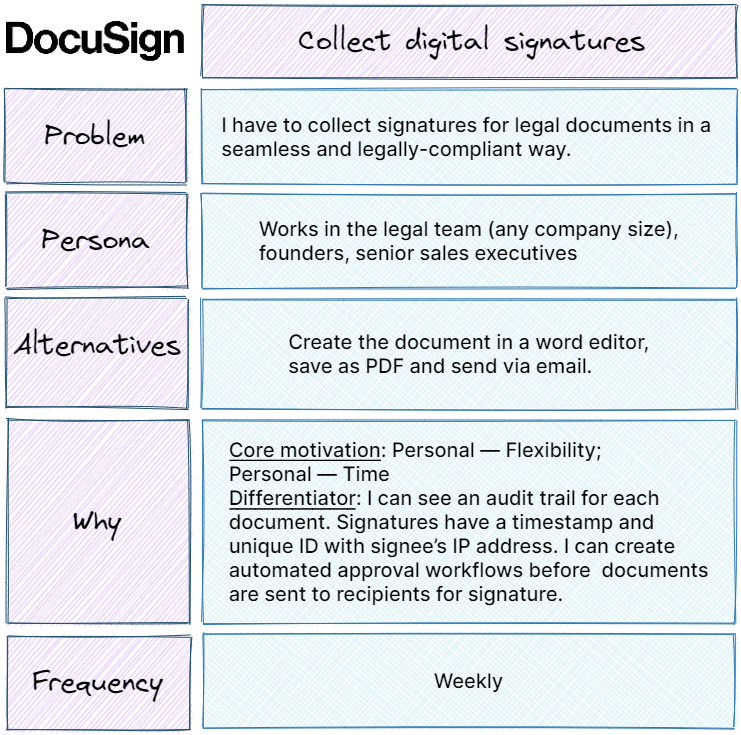

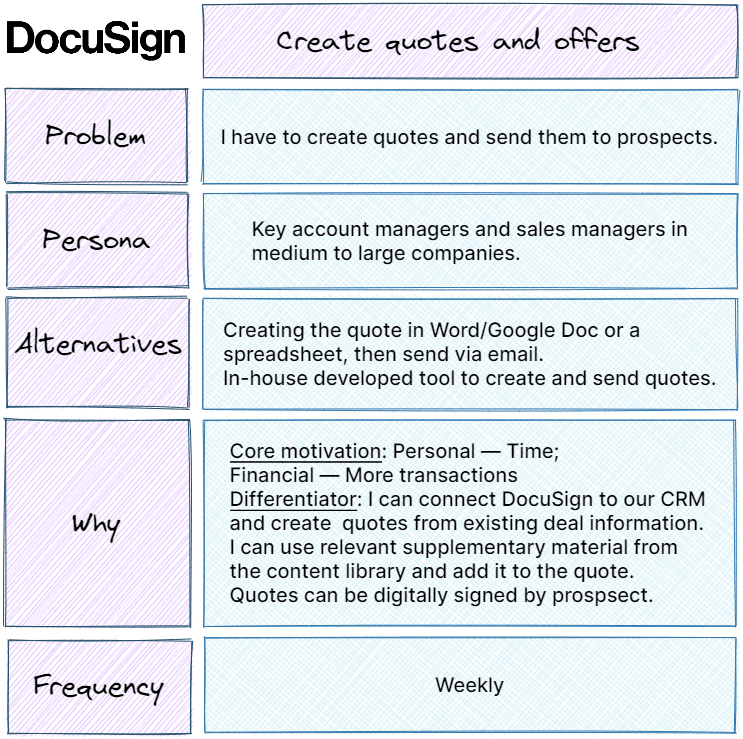

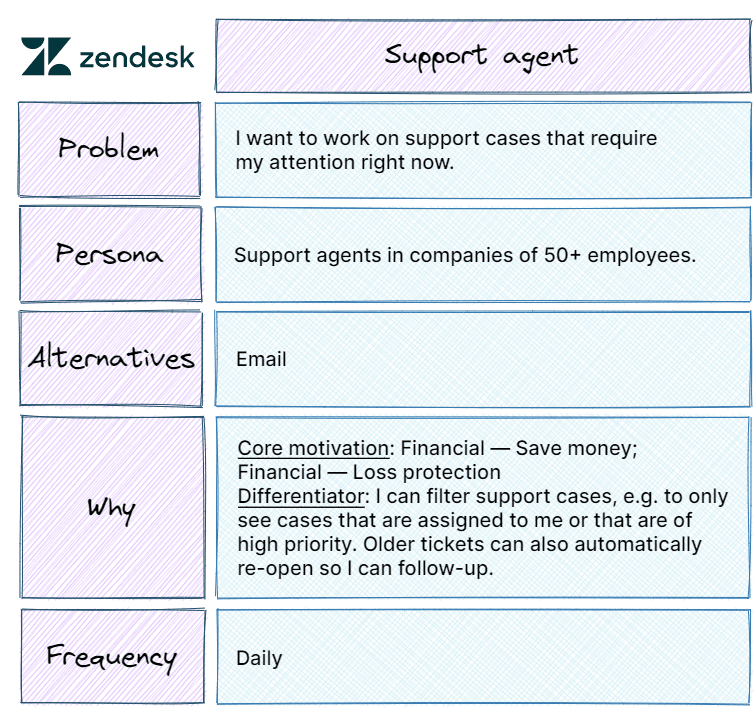

Let’s look at those four examples to see how the problem, persona, alternatives, and the why play together:

Casual hosts are people who own a second home, or maybe just have a large house with a spare guest room. They want to earn a side income by renting out these spaces but don’t want a long-term commitment.

Maybe they want to use their second apartment themselves as a vacation destination a few times per year, or they can earn more by renting by the day. That’s why they don’t put it onto the normal housing market and rent it out to classic long-term tenants.

The core motivation here is clearly a financial one — they want to get access to the pool of potential customers Airbnb offers.

Also, renting out through the platform requires only low effort, and the more often you do it — assuming good quality — the more new prospects you’ll get through Airbnb’s rating system.

One of the classic use cases for Pinterest is to collect inspiration for specific projects. Those can be weddings (e.g. table and venue decoration, invitation card design etc.), re-designing your apartment, ideas for a DIY project you’re working on, or design ideas for your garden.

The alternatives aren’t really compelling: You could get some fitting visuals through Google Images, dedicated communities such as subreddits, forums for gardening or DIY stuff, or sifting through dozens and dozens of YouTube videos.

The key differentiator of Pinterest is the almost infinite, on-demand supply of images around lots of interests and niches. Through the personalized recommendations you can also discover more related content based on what you like. And through “pinboards” you can organize and curate pins that you like.

Within this use case Pinterest provides information (e.g. all the wedding venue design ideas you have seen), as well as a sense of confidence. Since you have seen so many alternatives and possibilities, you’ll be more confident in the venue design that you ultimately choose.

Loom lets you record your screen and — if you want — simultaneously a recording of your front camera at the same time. You can then easily share this video with others a unique link.

A lot of people want to send personalized messages through email or text, maybe even with a screen recording. But it takes a long time to type out these messages, or to record and then send the video; which is only the screen anyway, hence not very personal.

This is the case for sales reps for sales pitches, product managers for product demos or messages to their team, or even support agents who want to record a quick walkthrough of the solution instead of typing everything out with a lot of screenshots.

With it’s easy to use solution, Loom provides the personal benefit of more flexibility in how to deliver your message, and a lot of time saved compared to the alternatives.

Thumbtack is a platform for consumers to hire professional services around the house such as plumbers, electricians, gardeners, or handyman services. They are so called “Pros”. The second use case is for small business owners to offer their services (see here).

Thumbtack is mostly used by your working professionals, usually in cities or suburbs. It provides flexibility: You can always get support right away once you have a job to be done. No need to ask around for referrals from friends and colleagues.

The large pool of Pros on Thumbtack also allows you to compare multiple offers which can be handy (no pun intended) especially for larger projects.

Really nailing down the why will take time. But as the other parts of your use case map, it doesn’t has to be perfect from the start (and probably won’t be). It’s important to have a decent understanding and then iterating and improving over time.

The challenging part when researching your why is that often times users themselves are not fully aware of the deep motivations that made them go for your product. And sometimes they might know it but don’t share every aspect of it.

A lot of people would be uncomfortable admitting they bought their Tesla as a status symbol and will mostly focus on the environmental aspect.

Or take Cybex: A German manufacturer of high-end baby strollers that’s positioning itself more and more as a lifestyle brand for parents. Within the last couple of years, they have become a status symbol for upper-middle class moms and dads.

If you walk around wealthier neighborhoods of Hamburg, Munich, or other large European cities you’ll see baby accessories with their yin and yang inspired logo everywhere.

Are the products of high quality and convenient to handle in a parent’s day-to-day life? Yes. Is the status signaled by carrying around products with their logo a major purchase motivation? Absolutely.

With this gotcha in mind you again have to turn to your healthy, i.e. happy existing users for insights. The following questions can guide you to uncover your users’ motivations:

- What is the healthy users' journey to your product? Some sample questions you could ask:

- How did you hear about the product?

- What made you try this product?

- When was it?

- Who were you with?

- Why did they choose your product over the alternative?

- Why did you stop using [alternative]?

- When did you stop using [alternative]?

- And in case they did choose the alternative over your product, when and why did they do so?

- When did you last use [alternative]?

- What made you choose [alternative] over the product?

- Who were you with?